“High performance” is shaping up to be even trickier to define when applied to housing. “Appropriate performance” is what we need.

What is a sustainable home? Well, we know one when we see one: this practice I co-lead has been wholly focused on designing sustainable homes for nearly three decades. But the rising tide of greenwashing is frustrating, it makes decisions harder for people who genuinely care about making choices that are better for them and their community.

Certified Passivhaus: a clear definition

“High performance” is shaping up to be even trickier to define and to render meaningful when applied to housing. At least “certified Passivhaus” is straightforward, thanks to a clearly defined standard and independent verification. Our practice has steadily leaned into designing Passivhaus projects since 2016 and this transparency is the one of things we really like about it.

But not all our projects fully reach the Passivhaus standard and even with some that do, the homeowner doesn’t go through with the last formal stage of certification. These become part of an important second category: not certified Passivhaus but way, way better than a home built to the legal minimum of the Building Code. They are easy to maintain at a comfortable temperature year round, use modest amounts of energy for heating and cooling and the indoor air quality is great.

What to call the nearly-Passivhaus?

These homes have all the bits you’d expect to see in a certified Passivhaus: mechanical ventilation, appropriate levels of insulation, quality windows etc and their real world performance has been accurately predicted. They don’t have the certified stamp.

So what to call those projects? A lot of people, including us, have been calling them high performance. That’s the recommendation contained in 16 pages of guidance just released from the Australian Passivhaus Association, an attempt to protect the use of the untrademarked Passivhaus term.

We do not agree. We have promoted the term in the past but as of today, “high performance” is dead to us!

Why? Because it intrinsically conjures up an idea of luxury, status, something nice to have but not necessary—and not obtainable for the vast majority. Analogies with fast cars seem inevitable.

A high performance car—pick your expensive marque of choice—is very expensive, very fast, handles like a racecar and offers many tangible and intangible extras. If the function of a car is to transport people and stuff from A to B, high-performance cars have a great many features beyond what is required to do that. They are necessarily by definition not for everybody, just the fantastically wealthy.

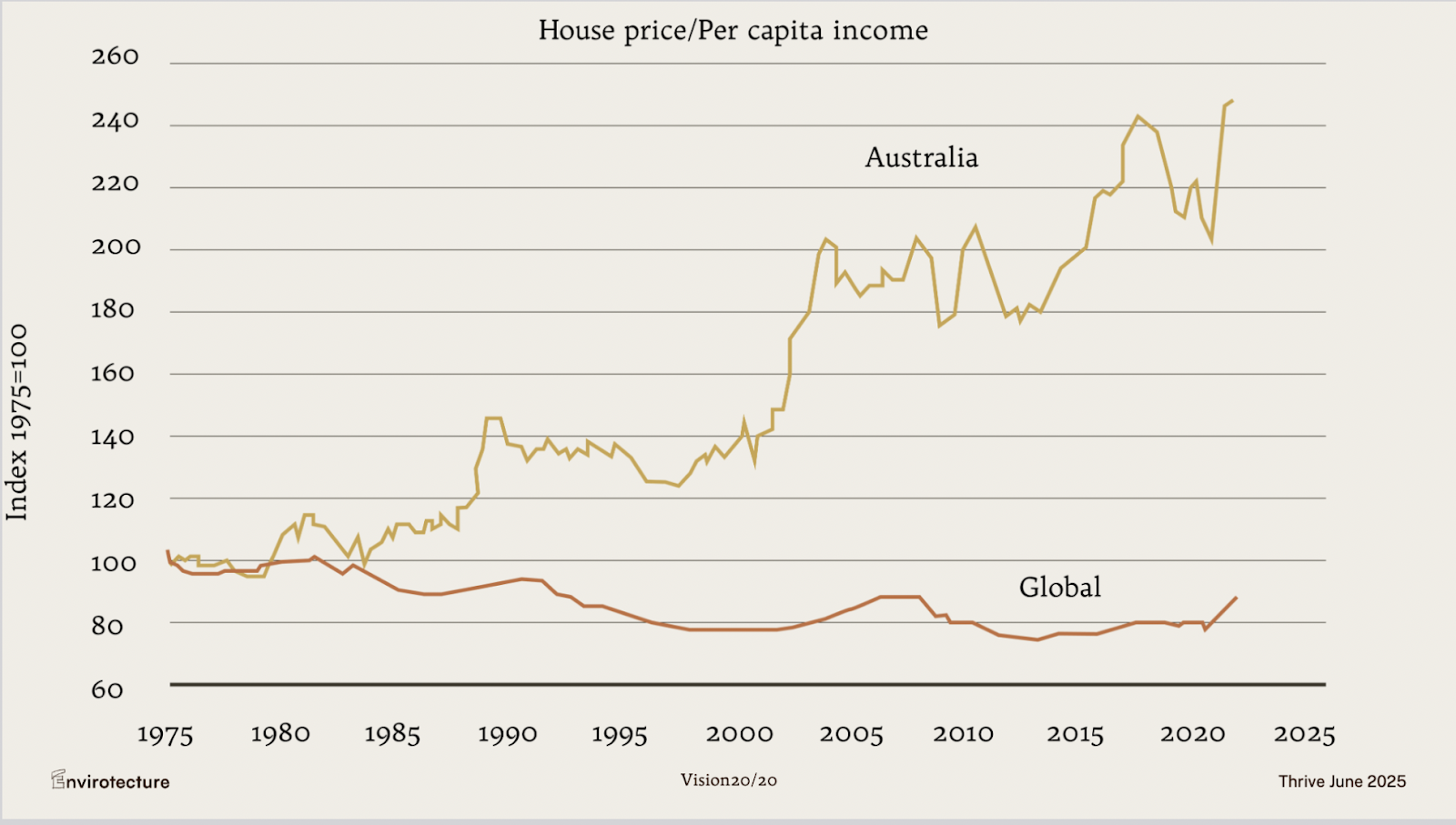

There is a societal lack of clarity as to the purpose of housing in this country. A realistic analysis of the Australian housing market suggests that housing is an investment product in which some people also live. Many would agree with me that this should not be the goal, but it’s hard to mount a serious defence given the evidence of how the market is behaving (and influencing people to behave).

We’ve ended up in a situation where only buildings’ economic performance seems to matter. (How’s your capital gain this quarter?) So why invest in better thermal performance, better comfort, better energy efficiency, if those types of performance don’t increase economic performance?

Australia’s building stock, including the newly built ones, on the whole fails to do basic things, like keep people warm in winter or cool in summer, prevent condensation and mould or provide even basic indoor air quality. In the face of this, people have started calling the relatively few buildings that do these things, high performance. It’s correct in that these buildings perform to a higher level than the woeful average, but it misses the point!

A new label: appropriate performance

If we are to have buildings in which we can be healthy and comfortable and which do not squander finite planetary resources, we need to stop implying such things are luxuries reserved for the fortunate few. Enter appropriate performance. A less sexy descriptor? Yes. But more accurate (dare I say, more appropriate)?

What is appropriate to expect from an Australian home? In our view, the following performance criteria should be the minimum:

- comfortable indoor temperature and humidity levels all year round

- modest-to-minimal energy bills for heating, cooling and hot water heating

- fresh indoor air without being forced to open windows when it doesn’t suit

- healthy indoor environment with low levels of CO2 levels, VOCs and other pollutants

- no condensation on the interior of the building structure

- no mould

- harvests renewable energy on site in a considered way

For millenia, humans and our ancestors have sought shelter: places safer and more comfortable than outside. Today, in many Australian locations at certain times of year, the unsheltered space (the outdoors) is both more healthy and more comfortable than inside. In our time of technological marvels and cleverness, this is nuts.

Our buildings should provide healthy, comfortable spaces as a bottom line—for everyone. So here at Envirotecture, we’re going to stop talking about such buildings in a way that implies they are a luxury reserved for the wealthy.

Appropriate performance for all!

Andy Marlow

,

Company

Andy joined Dick Clarke at Envirotecture as a young architect, gaining significant experience in designing genuinely sustainable buildings, both residential and non-residential, in Australia and overseas. After a stint at a large corporate practice, Andy returned to Envirotecture as a director in 2014. He went on to found Passivhaus Design & Construct in 2020, in order to make Passivhaus performance more accessible for more people.

Discover our people (and what it's like to work here) and awards we've won.

Explore our expansive library of resources for people interested in sustainable, healthy homes.